My Part in the Warsaw Uprising, 1944

Record of Society member Les (Lech) Gade’s experiences in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. As told to Reconnaissance editor John Muscat on 22 February 2018. Originally appeared in the Autumn 2018 edition of Reconnaissance, the Society's quarterly magazine.

Editor: After Hitler’s

occupation of Poland in September 1939, the Polish Government-In-Exile

in London sponsored an underground movement within Poland, including a military

force called the Home Army or Armia Krajowa (“AK”). As the Red Army approached

Warsaw in late July 1944, Soviet authorities encouraged the Polish

underground to launch an uprising against the Germans, promising all

necessary aid. For their part, AK leaders were concerned that Stalin would

extend the control he acquired over eastern parts of Poland to the rest of the

country, leading to the imposition of a post-war Communist regime.

Hoping to

take Warsaw before it was “liberated” by the Red Army, the AK acted on the

Soviet call to revolt. Under Command-in-Chief General Tadeusz

Bór-Komorowski and his chief of Warsaw forces Colonel Antoni Chrusciel, some

50,000 fighters launched an assault against the relatively weak contingent of

German SS and police units at 5:00 pm on 1 August (“W- Hour”). In

the opening phases they occupied extensive tracts of the city, protecting their

gains with an elaborate system of street barricades. But the Germans sent in

reinforcements and pushed the AK into defensive positions, subjecting them to

continuous air and artillery bombing for the following 63 days. In the

meantime, the Red Army overcame a German counter-offensive and occupied a

suburb across the Vistula River from Warsaw, but did not intervene. The

western Allies were refused permission to use Soviet air bases to drop supplies

on the insurgents.

Without external support, the AK disintegrated into depleted

and isolated units. They were forced to surrender when supplies gave out on 2

October. Bór-Komorowski and his men were taken prisoner and the Germans

deported Warsaw’s civilian population before reducing the city to rubble. The

Red Army finally occupied the ruins on 19 January 1945. The Warsaw Uprising was distinct from the possibly better known Uprising of the Warsaw

Ghetto in April and May 1943.

MY PART IN THE WARSAW UPRISING, 1944

|

| Les (Lech) Gade |

MY PART IN THE WARSAW UPRISING, 1944

Before the War

I

was born in 1930, so I was 9 years old when the Germans invaded Poland and

almost 15 at the time of the Uprising. I grew up in Warsaw with my parents and

two sisters, one older and one younger than me. We spent our summer holidays in

the country village my father originally came from. There was a lot of tension

prior to the German invasion on 1 September 1939. Hitler demanded a road and

rail route through the Polish Corridor between West and East Prussia. Poland refused.

There was a lot of worried talk and a general feeling that war could come any

time. At my primary school we had drills with gas masks and sticking plaster

was applied across the windows.

Our

home in Warsaw’s City Centre (Srodmiescie) was an apartment on Copernicus

Street, which further along merged with New World Street in the rear. In Warsaw

the street level of buildings were commonly used for shops and businesses while

residential apartments occupied the upper floors. They were mostly

square-shaped blocks around an internal courtyard with access through a gateway

on the street.

Our

apartment straddled an “L” shaped internal corner of the block, one floor above

a ground level shop. The living quarters were in one leg of the “L” and my

father Frank operated a tailoring workshop in the other. Suits and other types

of clothing were tailor-made in those days. My father’s business did well and

he was always busy. At various times he employed a regular worker as well as an

apprentice. When I reached school age, the local primary school was full so I

had to attend one in the next district, further east near the Vistula River.

This was a more working class area where the largest industry was dredging sand

from the river. It was a rough place and I was considered an outsider. I got

into a lot of scrapes. A couple of times my glasses were knocked off and I

ended up with a black eye. But I gave some black eyes in return.

The Invasion

I

still remember the first day of the war. It was a clear day. I recall seeing

bombers fly over our home. At first people said they were ours but then they

started dropping bombs on us. There were no air raid shelters at that time. So

we all huddled in the underground cellars which were a feature of Warsaw

buildings. They were used to store coal, a source of domestic energy,

especially in cold weather, as well as potatoes and other vegetables. Every

apartment owner had their own enclosed cellar area under lock and key.

Around 5 days into the war, we were subjected to lighter shelling and smaller ordinance. We could hear the whistling and bangs. But it didn’t take long for the Germans to reach Warsaw. Eventually there was constant heavier bombing and shelling. Things intensified when the bombers started flying over every day. I think they were mostly Stuka and Dornier dive bombers. I still remember seeing one shot down by Polish anti-aircraft fire. Unfortunately some of the anti-aircraft shrapnel fell onto and injured civilians. It was not uncommon to be caught in the open when a bomber struck, since there were no organized shelters. You just had to run into the nearest courtyard. Everyone carried gas masks.

|

| Central Warsaw under attack, 1939 |

Around 5 days into the war, we were subjected to lighter shelling and smaller ordinance. We could hear the whistling and bangs. But it didn’t take long for the Germans to reach Warsaw. Eventually there was constant heavier bombing and shelling. Things intensified when the bombers started flying over every day. I think they were mostly Stuka and Dornier dive bombers. I still remember seeing one shot down by Polish anti-aircraft fire. Unfortunately some of the anti-aircraft shrapnel fell onto and injured civilians. It was not uncommon to be caught in the open when a bomber struck, since there were no organized shelters. You just had to run into the nearest courtyard. Everyone carried gas masks.

Three

weeks after the invasion, Warsaw was surrounded by German tanks but the city

refused to surrender. So the Luftwaffe started a continuous and indiscriminate

campaign of terror bombing. We spent most of this time in a cellar facing

Copernicus Street. Eventually we felt the bombing start to ease off, so my

mother returned to our apartment to cook a meal. Straight away we heard a

single bomber dropping bombs, each bang coming closer. The apartment block next

to ours was a higher 6 storey building. It suffered a direct hit and collapsed

onto our apartment. My mother was killed. The apartment was destroyed and

everything caught fire, including my father’s equipment. Since none of our

possessions were in the cellar, we were left with nothing but the clothes on

our back. My father wasn’t with us at the time as he was a fire warden. A

fellow warden of his was blinded in the explosion that destroyed our apartment.

We all ended up in Copernicus Street. I remember the blinded warden in the

middle of the street asking for help. We were in danger as aircraft were flying

around machine gunning civilians indiscriminately. We ran for a bank further up

Copernicus Street. The lobby was full of people sitting on the floor. I

remember a young woman crying with her mother’s corpse beside her.

We moved onto the riverside district where my uncle lived, and I was put in his care. My older sister was sent to other relatives. My 3 year old younger sister was taken by her god parents, who moved out of Warsaw. I didn’t see her again until 1981. Things got so desperate in this period that people resorted to eating horse meat. A couple of days later, Warsaw capitulated.

Eventually my father found work and a place to live in New World Street around the corner from Copernicus Street. My older sister and I moved in with him. My father worked on the ground floor, renting 2 rooms from a 3 room apartment. He managed to salvage a sowing machine from the ruins of our home and took it to a Jewish mechanic for repairs. So he was able to start earning a living again. That first winter after the invasion was very cold and we only had light coats. Before the war my father didn’t drink or smoke, but now he started smoking. We ate fried onions for breakfast, it was all we had. Then it was off to school for the day.

We moved onto the riverside district where my uncle lived, and I was put in his care. My older sister was sent to other relatives. My 3 year old younger sister was taken by her god parents, who moved out of Warsaw. I didn’t see her again until 1981. Things got so desperate in this period that people resorted to eating horse meat. A couple of days later, Warsaw capitulated.

|

| German troops parade through Warsaw, 1939 |

Eventually my father found work and a place to live in New World Street around the corner from Copernicus Street. My older sister and I moved in with him. My father worked on the ground floor, renting 2 rooms from a 3 room apartment. He managed to salvage a sowing machine from the ruins of our home and took it to a Jewish mechanic for repairs. So he was able to start earning a living again. That first winter after the invasion was very cold and we only had light coats. Before the war my father didn’t drink or smoke, but now he started smoking. We ate fried onions for breakfast, it was all we had. Then it was off to school for the day.

The Occupation

As

soon as the Germans entered Warsaw, the terror started. They considered

themselves superior to Poles and showed it. At first German soldiers patrolled

the streets on foot in pairs. But the Underground began staging attacks on them

well before the Uprising in August 1944. So the Germans took stronger

precautions. Sometimes you would notice a street was blocked off because the

Germans and the Underground were exchanging fire. From 1942 the Germans began

rounding up say 20 people at random and throw them into prison. Placards would

be posted on walls naming the captured people with a warning that they would be

executed unless the attacks stopped. Inevitably the hostages would be brought

out to a public place and shot. The place of execution would be barred to

onlookers and the bodies were taken away. But afterwards you could see the

blood and bullet holes. Today Warsaw is full of monuments on sites where these

executions happened.

A German could do anything to a Pole and there was no legal recourse. Universities and high schools were closed. Primary schools were restricted to teaching the four R’s and the only post-school option was trade school. The Germans planned to reduce Poles to a race of menial workers. I returned to a primary school near my uncle’s place. The Polish teachers did their best to teach the kids as much as possible, and underground high schools and universities were conducted in secret. In essence Poland never formally surrendered and created the elements of an underground state.

|

| Execution of Polish civilians |

A German could do anything to a Pole and there was no legal recourse. Universities and high schools were closed. Primary schools were restricted to teaching the four R’s and the only post-school option was trade school. The Germans planned to reduce Poles to a race of menial workers. I returned to a primary school near my uncle’s place. The Polish teachers did their best to teach the kids as much as possible, and underground high schools and universities were conducted in secret. In essence Poland never formally surrendered and created the elements of an underground state.

My

father fought in the First World War but he didn’t like to talk about it. In

that era Poland was partitioned between Russia, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and

Germany. He ran away from home at the age of 14 to join the Polish Legion, which

fought on the side of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. When war broke out in 1914,

the Legion was set up from sporting clubs to fight the Russians. The Legion

marched into Warsaw on Armistice Day and declared a free Poland. So 11 November

became Polish Independence Day. During his four years in the Legion, my father

fought in eastern regions. When he was light-hearted he liked to sing songs

picked up from the Ukraine. By the Second World War he had a negative attitude

to anything military. He completely refused to get involved.

He

disapproved of me joining the Boy Scouts (or Cubs at my age) because in those

days it was seen as a preparation for military service. I was keen to be a

soldier and joined the Scouts without his approval. The scouting movement in Poland

was patriotic and militaristic. During the German occupation it was banned on

pain of death. Meetings and activities were conducted in secret, usually in

school after regular lessons or on weekend camping trips outside Warsaw. This

was dangerous. If the Germans found out, the participants would be executed or

sent to concentration camps. And the Gestapo had informers. But scouts were

called on to perform some underground tasks like carrying the illegal press

because they attracted less suspicion than adults. Around when I reached the

age of 14, the Scout masters gave us lectures on German guns. We were told

about Schmeisser MP38 and MP40 machine guns and other weapons. For a couple of

hours they showed us pictures and explained how they worked. There was no

formal military training in weapons handling, which began at a later age,

usually 15. I first learned about the Underground Polish Home Army, or Armia Krajowa (“AK”), from the Scouts.

You heard about it by word of mouth. Someone who got to know you would ask if

you were interested in the Underground.

I

finished primary school in early 1943 and was set to begin trade school in

1944. In the meantime I became an apprentice radio technician in a German

Telefunken radio factory in central Warsaw. I assembled portable radios for

German troops. I was technically still in the Scouts and attended meetings in

school rooms and sometimes in private houses. The teachers were in on it. We

were taught typical scouting stuff, badging, knots, camping, map reading,

compass, but it was all considered help for future military training. At one

point a fellow at the school asked me to come to a certain address where I got

the pseudonym “George”. Members of the Underground were known by pseudonyms.

But we were too young for our Scout group to move directly into the Underground

as some other units did. When I later joined the AK, I was given the pseudonym

“Leszek”.

The Uprising

When

“W-Hour” arrived at 5:00pm on 1 August 1944 [ed:“W” standing for wybuch, meaning “outbreak”], I didn’t

know anything about an Uprising. Someone in our scouting group just told me we

had to meet at an assembly point. I can’t remember who it was, we only knew

each other by pseudonyms. From memory the assembly point was the school, but

I’m not sure. I was told nothing else. Then all hell broke loose. New World

Street came under heavy German fire and fighting started. The streets were so

dangerous that people started kicking holes in internal walls of buildings to

use as passageways. It was safer than walking out in the open. I took shelter

in a cellar beneath our apartment block. All sorts of people were coming

through looking for shelter.

The

German fire and mayhem outside barred me from going in the direction of the

assembly point. I couldn’t do much. I was also afraid to tell my father. A girl

around my age was trapped in the same area. She asked me “are you in the Scouts”.

I said “yes”. She asked “what are you still doing here”. I explained that there

was no way of getting to my assembly point. She suggested that we climb out

through a small high window in a nearby garden area. It opened a way onto

Copernicus Street. So I gave her a leg up into the window and she dragged me

up. On landing in Copernicus Street we ran south and turned into a cross

street. We came under machine gun fire from a tall building opposite under

German occupation, so we had to scamper. We survived and ran west into Napoleon

Square, one of the main hubs of central Warsaw. The Post Office had just been

liberated by the AK. There was a lot of cheering and celebration. Further along

I saw a hotel on a street off the square guarded by a fighter carrying a German

machine gun. He was wearing the white and red AK armband. I told him I couldn’t

reach my assembly point. He referred me to his lieutenant, who just said “good

we need a runner”. So I never returned to my Scout group.

I was promptly sworn in as a soldier of the AK. I got a piece of paper for ID with my full name on it and my new pseudonym of “Leszek”. I was also given a white and red armband. My rank was private. There was no uniform, I wore my usual clothes the whole time. I discovered that the hotel was in fact Hotel Victoria, the official headquarters of Colonel, later General, Antoni Chrusciel, pseudonym “Monter”, commander of AK forces in Warsaw. He was also chief-of-staff to General Tadeusz Bor-Komorowski, pseudonym “Boor”, commander-in-chief of the AK. “Monter” was in charge of the Uprising and I was effectively on his personal staff as a runner.

|

| General Antoni Chrusciel, pseudonym 'Monter' |

I was promptly sworn in as a soldier of the AK. I got a piece of paper for ID with my full name on it and my new pseudonym of “Leszek”. I was also given a white and red armband. My rank was private. There was no uniform, I wore my usual clothes the whole time. I discovered that the hotel was in fact Hotel Victoria, the official headquarters of Colonel, later General, Antoni Chrusciel, pseudonym “Monter”, commander of AK forces in Warsaw. He was also chief-of-staff to General Tadeusz Bor-Komorowski, pseudonym “Boor”, commander-in-chief of the AK. “Monter” was in charge of the Uprising and I was effectively on his personal staff as a runner.

I never received a

weapon and in the first weeks of the Uprising I was something of an office boy.

A couple of days after I started, Hotel Victoria was bombed so headquarters

moved into the building next door, formerly a bank. Initially there were 3

runners and eventually 4 or 5. Any serious communication from “Monter” had to

be delivered by a runner. At some sites telephones were available but

vulnerable to interception by the Germans. Once the Uprising started a staff

bureaucracy or “kancelaria” emerged around “Monter”. Messages were constantly

being sent to various officials of the civil administration within the building

as well as commanders and fighting units in the field. I would just be given an

envelope with a person’s name on it. Most of the recipients were inside

headquarters. But once or twice a day I had to run the gauntlet of German

mortar shells, aerial bombing and snipers on my way to some command post behind

a street barricade or in a cellar or ruined building.

I operated within the part of Warsaw that AK command called City Centre Sector 1 Area 4. I recall some visits to a Colonel whose pseudonym was “Radwan”. I did run a few errands outside this sector to the Old Town until the AK withdrew. Earlier on we ran in pairs in case one got killed, but that practice was eventually dropped. I didn’t have to descend into the sewers as many AK fighters did. Often the destination was described as the barricade on the corner of such and such streets, and from memory barricades were numbered. Sometimes we were given the street address. How I got there I don’t know, as many of these areas were just rubble.

On a day-to-day basis I dealt with Monter’s adjutant, a Captain whose pseudonym was “Admiral”. He was a tall, good looking and polite man from the Polish cavalry. But the messages were handed to me by his underlings. I came into contact with “Monter” himself about half a dozen times. One day headquarters came under heavy aerial bombing. It seems the Germans found out about it. Since it used to be a bank, two underground floors were vaults lined with three feet of concrete. We were down there when we heard a Stuka dive bomber directly above us. The Stuka siren was so loud we could hear it clearly through the concrete. We braced ourselves as the bomb crashed through four above ground floors before exploding. Luckily it didn’t penetrate the concrete vault. General “Monter” was present on that occasion.

I operated within the part of Warsaw that AK command called City Centre Sector 1 Area 4. I recall some visits to a Colonel whose pseudonym was “Radwan”. I did run a few errands outside this sector to the Old Town until the AK withdrew. Earlier on we ran in pairs in case one got killed, but that practice was eventually dropped. I didn’t have to descend into the sewers as many AK fighters did. Often the destination was described as the barricade on the corner of such and such streets, and from memory barricades were numbered. Sometimes we were given the street address. How I got there I don’t know, as many of these areas were just rubble.

|

| AK fighters in the rubble of Warsaw |

On a day-to-day basis I dealt with Monter’s adjutant, a Captain whose pseudonym was “Admiral”. He was a tall, good looking and polite man from the Polish cavalry. But the messages were handed to me by his underlings. I came into contact with “Monter” himself about half a dozen times. One day headquarters came under heavy aerial bombing. It seems the Germans found out about it. Since it used to be a bank, two underground floors were vaults lined with three feet of concrete. We were down there when we heard a Stuka dive bomber directly above us. The Stuka siren was so loud we could hear it clearly through the concrete. We braced ourselves as the bomb crashed through four above ground floors before exploding. Luckily it didn’t penetrate the concrete vault. General “Monter” was present on that occasion.

One

of my worries in those days was night-time deliveries. You had to say a

password which could change every night. It would be distributed to all the

main units, which might not receive the news for 3 or 4 days. I had a lot of

trouble remembering the right one. If I got the password wrong, I could easily

have been shot.

Once

in the course of a delivery, I got caught in heavy shelling on Napoleon Square.

I heard the “bellowing cow” as it was called, a German rocket launcher which

made a loud screeching noise before launching. The projectile was a mixture of

explosives and an incendiary like napalm. I fell flat and felt the heat but it

just missed me. Out in the open there was intermittent and indiscriminate

mortar shelling and an ever-present danger of snipers in the lofts. From above

the loud sound of Stuka sirens was going all the time. I remember how Stukas

demolished the Old Town, they had a free rein to do anything they liked.

Another day I was walking along a street in central Warsaw when a mortar fell.

I was briefly blinded and deafened but otherwise didn’t suffer a scratch. I can

only speculate that I was so close to the point of impact that the shrapnel

flew over me. I suppose this is the closest I got to being killed. I discovered

long after the event that two of my maternal cousins were Lieutenants in the AK

and one was killed on the first day of the Uprising. The other died only

recently and received a Polish state funeral. But my biggest fear was being

burnt, that was worse than death. A field hospital operated in the cellars of

headquarters. At one time they brought in someone who was completely burnt, his

or her skin falling off. The person squealed like a pig.

After

the Stuka attack on the bank building, headquarters moved to the Palladium

Cinema on Marshall Street (Marszalkowska), parallel to New World Street. We

were based there for the last two weeks of the Uprising. There was less and

less to do. The euphoric mood of early days grew increasingly depressed. It

became clear the Russians wouldn’t intervene and there was little the Western

Allies could do. There were RAF supply drops but they were vulnerable to German

anti-aircraft fire. There was also a famous supply drop by a hundred American

Flying Fortresses on 18 September. This caused a lot of excitement but most of

the supplies fell into German hands. When we surrendered on 2 October, I

remember some German soldiers laughing and pointing at the American supplies.

Russian aircraft had engaged German planes in dogfights before the Uprising,

but afterwards were nowhere to be seen.

Still, we had to keep up government offices and a civil administration to show the Russians we were ready to be an independent nation. The Soviet military attachè to Monter’s command was a Captain Kalugin. He had a runner. We often crossed paths and waved at each other, though we couldn’t communicate in a common language. But I didn’t have enough to do. Being conscious of military procedure, I reported to Captain “Admiral” and requested a transfer to a fighting unit. He tried not to laugh and said “no, request denied”. He probably thought I was too young to risk my life at that late stage.

Aftermath

Still, we had to keep up government offices and a civil administration to show the Russians we were ready to be an independent nation. The Soviet military attachè to Monter’s command was a Captain Kalugin. He had a runner. We often crossed paths and waved at each other, though we couldn’t communicate in a common language. But I didn’t have enough to do. Being conscious of military procedure, I reported to Captain “Admiral” and requested a transfer to a fighting unit. He tried not to laugh and said “no, request denied”. He probably thought I was too young to risk my life at that late stage.

|

| Surrender of AK forces, 2 October 1944 |

Aftermath

We

were ordered to surrender on 2 October. The white and red armband was accepted

by the Germans as a legal uniform for the purposes of the Geneva Convention.

Some threw off their armbands and escaped as civilians. However I got separated

and found that the streets were lined with SS troops. I thought it was too

dangerous, so I kept my armband and surrendered as a POW. We were taken to

Germany in cattle cars and imprisoned in an old factory. We were subjected to

continuous propaganda. The Germans repeated that we were betrayed by the

Russians so we should join them in fighting Bolshevism. General “Boor” refused

and the rest of us followed suit. We were there for six months. Then we were

marched off to the middle of Germany before reaching a camp around twenty kilometres outside Essen and then to Stalag Fallingbostel XI-B prisoner-of-war camp near Bremen. After that we were taken eastward again, ending up in

a village near Hanover. We slept in barns. I remember waking up from an

afternoon sleep and noticing the German guards had gone. British tanks appeared

around a kilometre away. Next up we saw the German guards being led by British

Tommies with Sten guns. A British officer spoke to us and a car came to take

the Germans into captivity. I remember exchanging badges with a British

parachutist.

The whole civilian population of Warsaw was deported, some to the country, some to Germany as slave labour and others to concentration camps. My father never got involved in the fighting and even though we aren’t Jewish he was taken to the Natzweiler concentration camp in Alsatia. Later I learnt that he was subjected to medical experimentation and injected with a disease. He died there in 1945, before the war ended. The last time I saw him was before I climbed out that window on day one of the Uprising. For a long time I suffered from survivor guilt. I hated Germans, even Volkswagen cars, but I got over it.

|

| After the Uprising, Warsaw in ruins |

The whole civilian population of Warsaw was deported, some to the country, some to Germany as slave labour and others to concentration camps. My father never got involved in the fighting and even though we aren’t Jewish he was taken to the Natzweiler concentration camp in Alsatia. Later I learnt that he was subjected to medical experimentation and injected with a disease. He died there in 1945, before the war ended. The last time I saw him was before I climbed out that window on day one of the Uprising. For a long time I suffered from survivor guilt. I hated Germans, even Volkswagen cars, but I got over it.

In

my opinion the AK leadership had no option but to launch the Uprising.

Otherwise Stalin, who urged us to rise up, would have claimed he asked for our

help and we did nothing. That would have been his excuse to crush Poland. And

after five years of German terror, especially in Warsaw, AK troops would have

started it anyway.

I

spent the years from 1945 to 1949 in Germany. We were still formally part of

the Polish Army in Exile until demobbed in 1947. I refused to go back to Poland

under a Communist regime, so I accepted refugee status. I was given a choice of

emigration to the US after six months or to Australia right away. Australia

looked like a good option in that cold European winter. I have been an

Australian ever since, even serving in the Australian Army Reserve for five

years from 1958 to 1963.

APPENDIX A

In 2012 Les gave a lengthy deposition in Polish to the Warsaw Uprising Museum, which can be found here.

APPENDIX B: LES'S WARTIME DOCUMENTS

Document 1: "Schulerausweis". Student identity card issued by the German occupation authorities in Poland. Issued for the 1943-44 school year. At this stage Les was a primary school student.

Document 2: "Schulerausweis". Student identity card issued by the German occupation authorities in Poland. Issued for the 1943-44 school year. At this stage Les had progressed to grade school. During the German occupation of Poland, all universities and institutions of higher education were closed to the Poles. Nazi policy was to confine Poles to labouring or menial occupations.

Document 3: Armia Krajowa (Polish Home Army or Underground) identity card. This card was issued to Les around the second day of the Uprising, when he became a runner attached to the staff of the Armia Krajowa commander of the Uprising in Warsaw. Les's pseudonym is recorded as "Leszek".

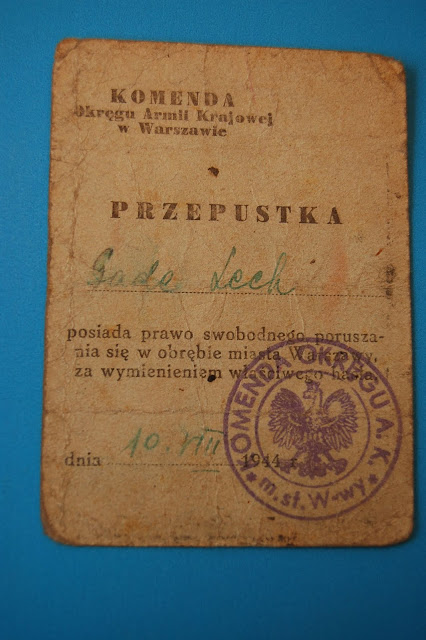

Document 4: Armia Krajowa entry pass. This pass gave Les access to the Uprising commander's headquarters.

Document 5: Stalag Fallingbostel XI-B (prisoner-of-war camp) record. When the Uprising failed, most of the Armia Krajowa surrendered to the Germans. They were accorded Geneva Convention rights as prisoners of war. Many of them, including Les, were incarcerated in the Fallingbostel XI-B camp near Bremen in northern Germany.

Document 6: Polish Armed Forces Identity Card. Following the defeat of Germany in 1945, Armia Krajowa members were absorbed into the regular Polish Armed Forces. Les was formally demobbed in 1948.

The Society's website is here: militaryhistorynsw.com.au

Why not join the Society? Visit the website's membership page here: http://militaryhistorynsw.com.au/home/membership/

APPENDIX A

In 2012 Les gave a lengthy deposition in Polish to the Warsaw Uprising Museum, which can be found here.

APPENDIX B: LES'S WARTIME DOCUMENTS

Document 1: "Schulerausweis". Student identity card issued by the German occupation authorities in Poland. Issued for the 1943-44 school year. At this stage Les was a primary school student.

Document 2: "Schulerausweis". Student identity card issued by the German occupation authorities in Poland. Issued for the 1943-44 school year. At this stage Les had progressed to grade school. During the German occupation of Poland, all universities and institutions of higher education were closed to the Poles. Nazi policy was to confine Poles to labouring or menial occupations.

Document 3: Armia Krajowa (Polish Home Army or Underground) identity card. This card was issued to Les around the second day of the Uprising, when he became a runner attached to the staff of the Armia Krajowa commander of the Uprising in Warsaw. Les's pseudonym is recorded as "Leszek".

Document 4: Armia Krajowa entry pass. This pass gave Les access to the Uprising commander's headquarters.

Document 5: Stalag Fallingbostel XI-B (prisoner-of-war camp) record. When the Uprising failed, most of the Armia Krajowa surrendered to the Germans. They were accorded Geneva Convention rights as prisoners of war. Many of them, including Les, were incarcerated in the Fallingbostel XI-B camp near Bremen in northern Germany.

Document 6: Polish Armed Forces Identity Card. Following the defeat of Germany in 1945, Armia Krajowa members were absorbed into the regular Polish Armed Forces. Les was formally demobbed in 1948.

The Society's website is here: militaryhistorynsw.com.au

Why not join the Society? Visit the website's membership page here: http://militaryhistorynsw.com.au/home/membership/

.png)

.png)

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment